Skeleton watches are timepieces that have undergone skeletonisation. In horological terms, this is the removal of superfluous material from the movement. This draws more attention to the intricate key components of the movement, but, oxymoronically makes the watch appear more complex. This is best described by the saying “less is more“: the less material there is, the more “watch” you can see. It’s a horological technique that has been around for longer than most would think, and nowadays is present in timepieces from all over the spectrum; from mainstream pieces to hyper-exclusive iterations.

Although the practice has been around for a few centuries, it has only just recently become a horological technique to pull off easily for large scale manufacturing.

Early Skeletonised Timepieces

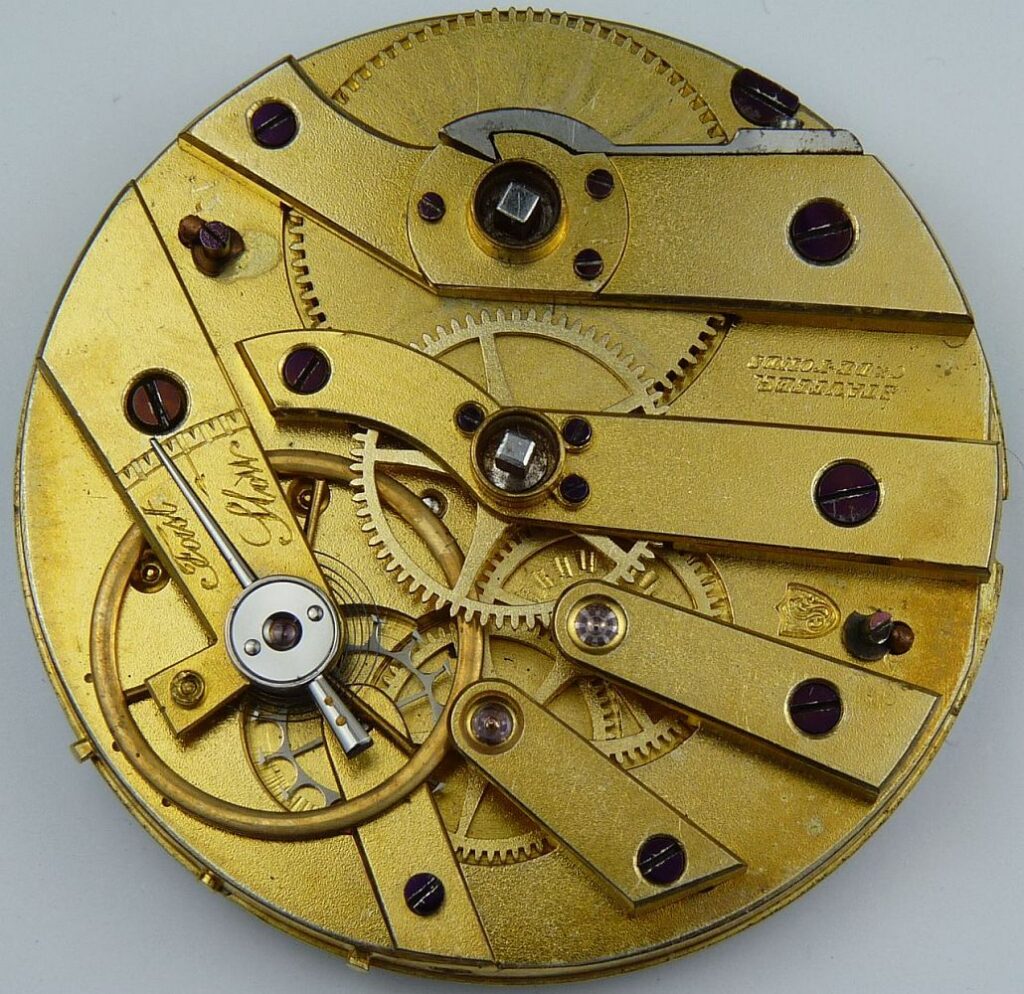

The first recorded use of the skeletonisation technique dates back to 1760, when the Frecnch watchmaker André-Charles Caron constructed a pocket watch with a balance bridge that was surface finished, engraved with his last name and, most importantly, visible. This was the unique design motif of the piece. (See photo below)

This design choice was deliberately made so that the owner of the watch, along with whoever might admire it, could see the internal mechanisms for both aesthetic preferences and personalisation purposes alike.

Even though the technique was employed on just one portion of the movement, this was the earliest iteration of skeletonisation that would pave the way for the method that we are familiar with today.

André-Charles Caron garnered the interest and the following of fellow watchmaker, apprentice and brother-in-law, Jean-Antoine Lèpine.

This equally talented French watchmaker, however, did not make his name in the horological world by following the skeletonised design. Instead, Lèpine made his mark in the watch industry by his various technological innovations, most importantly, the invention of the Lèpine Caliber. This consisted in the separation of certain parts of the movement by a series of bridges – a widespread technique present today.

Gaining traction

Alas, the art of horological skeletonisation was not a huge hit unti many years later. The technique came back onto the scene and began to gain traction in the 1960s, when the Swiss watch industry, amidst the Quartz Crisis, was trying every single possible method to prop the market up.

In this period, many brands invested their time (and hope) into adopting and developing this technique with the aim of the wearer taking an extra moment to appreciate the quality of the craftsmanship in the mechanical movement thanks to an “open” visible dial.

Complexity, risks and diversity

In short, to make a skeletonised watch, you want to strip the movement of as much metal as possible, whilst making sure that it still functions!

By making the watch more lean, slimming down bridges, gears and leads, you are left with only the bare essential components of the timepiece.

This is no smal feat, however: skeletonisation is a technique with many risks and complexities, both mechanically and design-wise.

Perhaps the most complicated aspect of skeletonisation lies in the watchmaker’s ability to carefully – sub millimetrically even – shave off this “superfluous” metal. This is because the correct and proper operation of the movement is heavily influenced by the distribution of mass within the caliber, which, is a very difficult accomplishment when you are stripping the watch of as much material as you can.

Up until the advent of modern technologies, this was an incredibly difficult, complex and strenuous task which required the artisans to undertake numerous and labour intensive trials.

This is why skeletonised watches dating to before the latter half of the 20th Century are very few and far between.

This technique does little (if anything) to actually improve the technical performance of the watch, and is purely for aesthetic purposes. As previously mentioned, it allows for every single tiny component of the mechanism to be on full display.

Which brings us onto another fundamental complexity, and quite a risky one at that, too.

All the eyes are on the movement, and so the watchmaker must account for immaculate finishing of every single minute detail and component, leaving no stone unturned.

Indeed, skeletonised watches are much more than “simply” stripping down the internals. Watchmakers strive to display the full capacity of their craftsmanship by – in many cases – hand finishing each and every component with nothing more than a file, bulin and a lot of patience and skill. In order to pay homage to these efforts, if you’re going to buy a skeletonised watch, be sure to do it right: choose one with a high quality finish.

Although nowadays mainly the higher end of skeletonised watches are hand-finished and decorated, it would be foolish not to acknowledge the advances in the field that new technologies have brought with them.

For example, one very significant innovation came in the form of a software that calculates both the maximum amount of material that could be removed whilst also optimising the manufacture of components so that they are already “reduced” and as “lean” as possible. This hugely decreased the number of man-hours and allowed for “pre”-skeletonised movements to be manufactured first-time.

Richard Mille’s use of bridges

These advances in technology allowed for Richard Mille to create their own type of skeletonisation, synonymous with their brand: a technique that many other watchmakers have since adopted.

Born in 2001, Richard Mille’s identity is closely tied to skeletonised horology, both from a “weight-reduction” perspective as well as from a design point of view: it is a fundamental part of their DNA.

In many of Richard Mille’s movements, the sinkers have been replaced by an intricate system of bridges (naturally, as lightweight as you can imagine – it’s Richard Mille we’re talking about, here) which support all of the components inside the case.

This innovation, material science aside, propelled Richard Mille to the forefront of horological development. To this day, they are regarded as the pioneer of lightweight sports watches.

In fact, the brand went as far as holding the entire mechanism in place with series of titanium pulleys and cables which drive the movement, significantly improving its shock-resistance capabilities.

Let’s have a look at the pieces which best represent the art of horological skeletonisation

Santos de Cartier Skeleton

Lately, Cartier has had a major comeback. The most iconic models, particularly vintage ones, have been worn be the most celebrated people in art, film, music and politics.

In 2018, it was the Santos that underwent Cartier’s process of skeletonisation. The legendary watch was made for Cartier’s aviator partner, Alberto Santos Dumont, accompanying him on his flights during the early 1900s.

The case measures 28x28mm and by default comes on a classic Cartier leather strap. It is also unmistakeably Cartier from it its sapphire cabochon crown cap, complimenting the blue hands.

The movement is none other than the manually wound in-house 9611MC, made visible by the skeletonised bridges that also act as the traditional Cartier roman numerals.

Vacheron Costantin Squelette Les Cabinotiers Minute Repeater

Designed and manufactured by Les Cabinotiers, sort of like the Navy SEAL Team Six of Vacheron Costantin (click here to learn more), this timepiece is simply breathtaking: only 15 were made in 2006.

This is an exemplary piece of horological skeletonisation: every single (remaining) component has been tirelessly hand-finished.

The Platinum case measures 37mm in diameter: an impressive figure considering the fact that it houses an incredibly beautiful and equally technically advanced caliber.

This manual movement is the cal. 755SQ, an ultra-thin movement with an integrated minute repeater which is entirely visible to the wearer, thanks to the impressive artisanal skeletonisation.

Flipping the watch over, the transparent caseback better displays this marvellous minute repeater (a complication which we’ve discussed here) as well as the “hollow” bridges and other hand-worked components which animate the timepiece.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Ultra-Thin Skeleton Steel

One word: simplicity.

You know the “less is more” phrase we used previously? Well, this is exactly what we were on about. This Audemars Piguet Royal Oak is a very special one: limited to only 100 pieces upon its release at the 2017 edition of Baselworld, this is every skeletonised watch collector’s dream. It embodies the very essence of an immaculate skeletonised dial.

The movement which powers this Royal Oak is the manual cal. 2949, which, after some slight technical slimming-down, measures a paper-thin 4.46mm thick, allowing for the case to be an equally slim 8.95mm.

The main attention grabber of this piece is the symmetry of the dial. Just look at it: everything is perfectly in line with its central axis.

Starting from the 12 o’clock position, we find the main hairspring. Moving downwards, we have the hour and minute gears, and at 6 we have a perfectly suspended minute Tourbillon.

Although we have mentioned its symmetrical features, they are intelligently juxtaposed by all the gears and various mechanisms being packed into the right hand side of the dial, meanwhile the supporting members, which are entirely visible throughout, are positioned on the left, almost like a Ying-Yang effect.

Patek Philippe Calatrava Skeleton Ultra-Thin

This article wouldn’t be complete without giving a nod to Patek Philippe.

In this very famous iteration of the Calatrava, the movement that makes the ref. 5180/1R beat is the ultra-thin cal. 240. This is an expertly hand-crafted, totally skeletonised piece which stands alone on this list as the only automatic watch.

The Swiss Maison claims that a minimum of 130 man-hours are put into creating this masterpiece. To better understand the work that is undertaken, have a look at the main cylinder inside the balance-wheel, shaped into the Calatrava Cross; or perhaps the masterful handwriting of the engraving bearing the Patek Philippe seal on the rear rotor.

The 39mm rose gold case is accentuated by circumferential supporting beams, holding the movement perfectly central. Combined with the many curled and bow-like decorations (naturally, all hand-made), it creates a “floating” effect; perfectly mirroring an item on display at a museum, or better yet, an art gallery – where this piece belongs.

We could go on all day making extensive lists about skeletonised watches, so we’ve limited it to just a short collection. Naturally, there are so many to choose from, with different versions, interpretations and degrees of skeletonisation.

Which one’s your favourite? Whether it’s on this list or not, let us know in the comments below!

– Translated by Patrick R.